I turned my head, and for a split second, everything turned white.

The moment of truth had arrived. The epiphany. A fraction of a second with a blinding flash, when everything came together.

I would survive. I would marry and have a good life. At 26-years-old, on April 5, 1980, I knew that the story would end happily. I’m Jewish.

Oh, but what a journey to get there, in a Tjolotjo beer hall in Rhodesia turning to Zimbabwe.

This was not a typical setting for a nerdy guy from Vancouver, Canada, with incredibly poor social skills and plenty of identity confusion.

There were perhaps 100 to 150 individuals in the room drinking Chibuku, the thick African maize beer. Tjolotjo is a tribal village/police camp in Western Zimbabwe, about 100 km from Bulawayo, the country’s rail and commercial hub, where I had lived for 16 months as a journalist and sub-editor.

The country would become Zimbabwe about two weeks later, and I would leave for home at the beginning of that May, culminating a six year journey from the University of British Columbia’s Ubyssey student newspaper where I struggled to learn the news writing craft.

My objective on this fateful Good Friday: To see how peace had arrived in an area at the centre of a seven-year insurgency.

I had made my way to Rhodesia in November, 1978 with a simple goal: To live through the war’s conclusion as a foreign correspondent.

To achieve this objective, I needed to be quite creative. First, no one would offer a 25-year-old guy working on a tiny Alberta newspaper, the Medicine Hat News, a foreign correspondent’s job.

But I could ask the newspaper chain if they could use a freelance “stringer” — and I had some knowledge of Africa, having overlanded after graduating from university through the Sahara, Congo, and then down to Rhodesia/South Africa.

The letter from the news service director arrived a couple of weeks later, inviting me to meet with the company’s full time Africa correspondent in Nairobi, Kenya. And I had managed to save about $5,000, enough for an open return ticket to Africa and about a month’s living expenses.

In Nairobi, I learned a hard truth. If I entered Rhodesia and declared myself as a journalist, I would be put on the next plane out. So after making my way down the continent with a stop in Rwanda (where I filed my first story to the news agency), I crossed the border by train from Botswana to Rhodesia, declaring myself as a student.

In Salisbury (now Harare), I quickly realized two things. One, the war would indeed end, sometime in the foreseeable future. Two, it would not end in a month.

So I set out and looked for work, applying at the local daily newspaper publishing organization, saying I would be happy to work in Bulawayo, a gritty, industrial city with a long-established end-of-the road daily newspaper. We worked in a 20’s era two storey building on ancient desks, with bic pens, and linotype machines clattering in the back. (Sanctions meant that the newspaper’s technology lived in a 1964 time-warp almost 15 years later.)

The Chronicle offered me a job as a sub-editor. I visited the immigration department to say I had been hired as a trainee. This white lie led to a work permit marked “journalist” — and the beginning of my expatriate life in the war-torn country.

These weren’t perfect months. Social awkwardness and blunderous behaviour led housemates in the shared “mess” to push me out. At one point someone saw my writing for the Canadian news service and reported me to the police.

I learned there was a problem when the newspaper’s assistant editor, Leo Rissen, called me into the office for a serious yelling-to. “Mark, get in here,” he said, warning me that he had been tipped off about the police inquiries. He also made clear that he was also Jewish, and had survived – in his case, escaping Europe through Shanghai, China before the Holocaust.

I called the police, said I would not write any more, and they let me go. (Probably it didn’t hurt that I was indeed legally in the country with a proper work permit.)

I then spent several months working my evening shift job at the newspaper, turning Robert Mugabe into an “external terrorist leader based in Mozambique,” drinking too much with my sub-editor peers at lengthy dinner-hour breaks, and failing miserably as a motorcycle mechanic. I managed to hammer a piston into a cylinder. I never saw any actual military conflict – my immigrant visa had a military service exemption that would expire only after the war’s conclusion – but I certainly experienced the home front story first-hand.

As these world and personal events were unfolding, my father took ill and died in Vancouver. I didn’t know he was seriously ill until 12 hours before learning of his death. Back then, the overseas phone (if you had one) was reserved for life and death matters – and the only form of personal communication was postal mail, that took months, and for which my mother and siblings did not inform me of his declining health.

I flew home to Vancouver for the funeral. My mom asked me to remain home but dad’s death occurred just as the war was indeed ending. I knew I had to return to see the story to its conclusion.

The next four months were incredibly intense, with ups and downs, social pain, personal growth, incredibly intense reading, and history unfolding in front of my eyes. I was also discovering my moral compass and personal values, appreciating my respect for women as I began to comprehend humanity’s universal elements.

This was a place of war and peace, nationalism, racism, religious heritage and identity, wealth and poverty – and I was part of the story; living through history in real time.

That Good Friday in Tjolotjo turned into quite a wild night. As we drunk, a prostitute offered her services, then offered herself for free (I declined). A truly big, tall and angry man said the wrong tribe won the war of independence and there would be more fighting. I prepared to spray him with a can of Raid, until a runty guy next to me tugged on my shoulder and suggested that wouldn’t be such a good idea.

My camera went missing. I stood on a table and firmly said, “I expect my camera to be returned this evening” — then continued drinking the thick and strong African beer.

An hour later, a police van pulled up with four guys in shackles, including the guy who had warned of continuing warfare. He had stolen my camera. But this was a police camp, and everyone knew where everyone lived, so it wan’t hard for the other police officers in the room to figure out who had committed the crime.

The next day, the Bulawayo Chronicle fired me. (It is rather obviously against the rules to get into drunken altercations at police camps.) I filed my story to Southam News (see below), followed Prince Phillip around Bulawayo and joined the international press corps on a British Royal Air Force jet back to Salisbury for the independence day celebrations. A few weeks later, I returned home to Canada, with stops in Ouagadougou Upper Volta (now Burkino Faso) and Liberia, just a week after a military coup there.

I had proven myself as a foreign correspondent. That Good Friday in Tjolotjo, I realized I had some courage, intelligence and integrity and could make my way in life.

Here’s the story I wrote after that fateful day.

The ending, unfortunately wasn’t so happy for the Zimbabweans. The tribal insurrection indeed happened, and Robert Mugabe resolved it by inviting the North Korean Fifth Army to help break it – with upwards of 20,000 deaths in 1981-2.

TJOLOTJO, Zimbabwe — Anthony Brownlee-Walker sat in the yard of his official district commissioner’s residence and said: “Now we’ve got to start all over again.”

At the other side of this remote administrative settlement, Lameck Bulle sipped on a beer and described how he is working with the district commissioner to reopen schools for 200,000 black tribesmen.

A few months ago, Brownlee-Walker wanted to put Bulle behind bars. And Bulle, a general trader, was providing hidden support to hundreds of guerrillas bent on destroying Brownlee-Walker’s administration.

Now they talk in terms of peace, independence and the massive job of rebuilding in the area where, for years, fear ruled the lives of black and white alike. Memories die hard, however.

By the end of Zimbabwe’s seven-year guerrillas war, hundreds — possibly thousands — had died in this region, though exact casualty figures are unavailable and police say many simply “disappeared.”

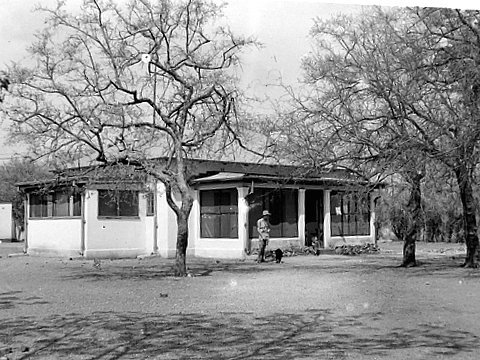

Tjolotjo became a heavily fortified outpost, with security fencing around all the white houses and sandbags and high security walls in prominent places.

When the ceasefire was signed last December, guerrillas loyal to Joshua Nkomo (now minister of home affairs in the new government) virtually controlled the region, reached by a winding 100-kilometre road from Bulawayo, the commercial centre of western Zimbabwe.

Nkomo’s men were able to close all but one of 73 schools after they arrived in 1976 and 1977. Almost all other forms of rural civil administration collapsed.

The security fencing still remains in Tjolotjo; 200 guerrilla renegades are still in the nearby bush.

Several blacks in the community say they will never really be happy until a member of their Ndebele tribe is Zimbabwe’s prime minister. And others say change is coming too slowly in the economic, social and political system.

But the fear that once ruled Tjolotjo is disappearing.

The white in charge of the local police detachment — his new boss is Nkomo — says there will be little trouble rounding up the dissidents once army units with ex-guerrillas move in.

“I personally feel much easier about the whole situation,” said Brownlee-Walker, who is staying at his post for the time being despite the change in administration.

And blacks like Bulle, district secretary for Nkomo’s Patriotic Front Party, talk freely with a white visitor where a few months ago they would have shied away, fearful of police and guerrilla reprisals.

Rebuilding is taking time. Brownlee-Walker says rebel guerrillas are discouraging tribesmen in the bush from coming forward, though representatives of Nkomo’s party were to visit the area to tell the people to return to a normal life.

Bulle said he was “born” a supporter of Nkomo. But he is not interested in great social changes, despite the socialist policies of the new government. “We must work legally to get some property,” he said.

Marxism and “liberation struggle” are not in his vocabulary. “What we wanted was any type of black man to take over Rhodesia — to make it a black Rhodesia,” he said.

Brownlee-Walker, meanwhile, remembers joining the civil service 15 years ago, shortly after Ian Smith declared independence unilaterally, and promised that blacks wouldn’t rule the land for 1,000 years.

“I think everything we have ever done has been for the benefit of the tribesman although he might not have appreciated it at the time,” he said.

“Everything we have built… I suppose they (the blacks) saw it as being representative of the white man … and knocked it all down… and now we’ve got to start all over again.”